EVERY DAY, President Donald Trump gives fresh reasons for Democrats to rue their election loss in 2024. The failures of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris mean that everything they professed to care about—the transatlantic alliance, the state’s capacity to improve society, the rule of law—is being unwound. Democrats spent years declaiming that a second Trump presidency would be catastrophic, an existential threat to American democracy. And yet more Americans preferred him to the alternative the Democratic Party set before them. Understanding how it all went so wrong would seem to be a priority.

You would think. But watching the succession proceedings at the Democratic National Committee a few weeks ago did not inspire much confidence. In his farewell address, Jaime Harrison, the outgoing chairman, proudly recounted a story about an encounter with donors who had expressed doubts about Ms Harris. “In all due respect, you are not worthy to even tie her shoes,” he told them. He continued fawning: “We should be thanking her every single day for all the hard work and effort she put in to fight for our democracy.” The next day, his successor, Ken Martin, took the reins of the party apparatus by demonstrating similar incapacity for introspection. “Anyone saying we need to start over with a new message is wrong,” Mr Martin had told the Democratic mandarins who elected him. “We got the right message.”

Others think that the party’s problems run deeper. “Anyone who just says, ‘The message is fine, we just didn’t get it out there,’ is very naïve about the problem,” says Seth Moulton, a Democratic congressman from Massachusetts. “It’s just an excuse for doing nothing and maintaining the status quo. Good luck with that. We’ll keep losing.” Increasing educational polarisation has realigned American politics—and not in the Democrats’ favour. While Ms Harris improved her margins among white, college-educated voters, she lost ground among almost every other important group: women (slipping five percentage points compared with 2020), those without college degrees (-8 points), Hispanics (-15 points), African-Americans (-16 points), the young (-20 points). Democrats once dreamed that demographic change would guarantee political dominance; instead it could be a nightmare.

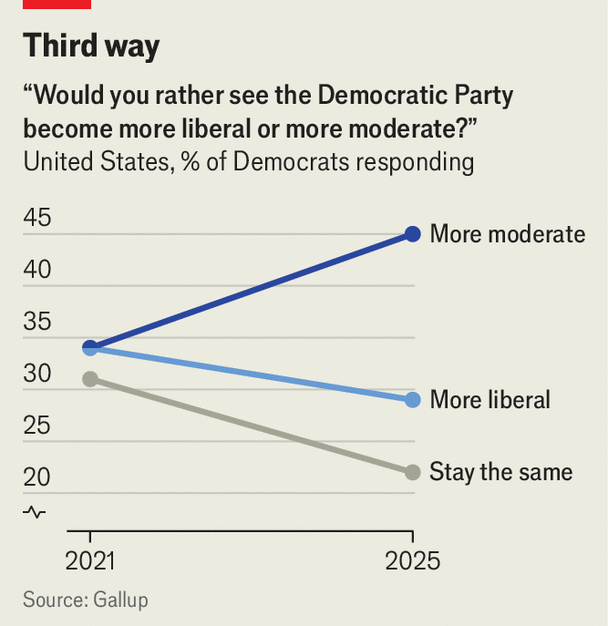

After any major loss, political parties often go through a warring-factions period. After Mr Trump’s first victory, a massive resistance movement benefited the party’s progressives. They achieved their apotheosis in 2020, when presidential hopefuls tripped over themselves to propose new trillion-dollar spending packages, while ideas about systemic racism and white privilege became voguish. This time round, though, the moderates are ascendant, arguing that the party veered too far left and turned off the non-white and working-class voters that were the party’s traditional power base. “We’ve turned into what I call the ‘shame on you’ party: You can’t drive that car, you can’t eat that food, you can’t use that word, you can’t work in that industry,” says Adam Frisch of Welcome PAC, a group that aims to elect moderate Democrats in difficult districts.

There are subtle signs that the balance is shifting. Based on their lack of protest, elected Democrats seem to have tacitly accepted that they lost the culture wars over immigration policy, over trans issues and over diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). But there is general unwillingness to repudiate these prior stances. “We’re afraid of difficult conversations, and we’re afraid to go against the extremist positions of many of the interest groups,” says Mr Moulton, who provoked a protest rally in his home district for breaking with his party and arguing that trans girls should not compete in girls’ sports. Some progressives also worry that identity politics went too far. Faiz Shakir, the presidential campaign manager for Bernie Sanders in 2020, says the party has successfully presented itself as “multiethnic…but not working class: a party that’s much more concerned about diversity and equity inclusion efforts” than economic justice. Interest groups advancing abortion rights, anti-racism, environmentalism and immigrant rights have been quieter in the face of such criticism, but they still retain considerable influence over Democratic politicians and, perhaps even more importantly, their staffs.

Chart: The Economist

In American politics, spells in the wilderness run at least two years—until the midterm elections. When a party’s representatives are in the minority it is difficult for them to demonstrate resistance without emphasising impotence. James Carville, a provocative Democratic strategist, has counselled the party to “play dead” and let the chaotic experience of Trump-led governance play out for itself. Some would say that Mr Carville’s advice is already being heeded. Hakeem Jeffries, the Democratic minority leader in the House, has said “We’re not going to swing at every pitch.” In fact, Mr Jeffries has spent some of his time on a book tour promoting his illustrated book for children, “The ABCs of Democracy”, and hosting a roundtable of social-justice groups in defence of DEI.

In defence of Mr Jeffries (and his Senate counterpart Chuck Schumer), the job of congressional leadership is to whip caucuses, fundraise and recruit promising candidates—it is not to set the intellectual direction for the party or even to excel at media appearances. There is some wisdom to Mr Carville’s advice on imitating possums. Political scientists describe public opinion as thermostatic—going cold when politicians go hot (and vice versa, ad infinitum). That suggests that, unless the party completely implodes, they will have a strong showing in the midterm elections in 2026. But until a presidential candidate is chosen for the next election, what the party stands for will remain contested.

Outside of the ancien régime, there are already efforts to generate fresh ideas. “We have to go on offense by contrasting the chaos and corruption of this administration with cost of living for Americans, which is going to go up under his tenure,” says Jake Auchincloss, another Democratic congressman from Massachusetts. He argues that rather than offering voters light populism on cultural issues—“Diet Coke” when the richer version is already at hand—“our economic telos as a party should be treating cost disease, particularly in housing and health care”.

Groupsthink

And if anything, resistance is livelier outside Washington. State attorneys-general in Democratic states were better prepared for Mr Trump’s return to power and have nimbly reacted to even his more unpredictable actions, such as letting Elon Musk rampage through the federal bureaucracy. The American Civil Liberties Union (aclu) has worked with blue cities and states to set up “firewalls for freedom” that hinder the federal government’s efforts to restrict abortion or enact deportations. The resistance “doesn’t look the same as last time” because there are fewer rallies but “in fact, it’s actually more strategic and more impactful,” says Deirdre Schifeling of the aclu which has sued the administration 14 times already.

Progressives are also slowly reckoning with the refutation of their theory that identity politics and expansive state spending would galvanise America’s proletariat. In fact, the dispossessed were repelled. Sorting out how to get them back is the essential task of the party. It will have a few years to ponder how to do it. ■